Radish to romanesco: A year in vegetables

February 20th, 2025

4 min

This article is brought to you by Datawrapper, a data visualization tool for creating charts, maps, and tables. Learn more.

Hi ✌️ I’m Julian, developer on Datawrapper’s app team — and a movie enthusiast. Today I am scientifically investigating the burning questions: Are franchises actually getting worse? Are they taking over the industry? And how bad is all that for cineasts?

Film series have been around for as long as the medium of film itself, but in recent years they’ve been the subject of increasing attention and controversy. Since purchasing the rights to big franchises like Marvel and Star Wars, Disney has been pumping out new installments. The financial payoff of this strategy has led other big production companies to try to replicate Disney’s success — a process that some consider a paradigm shift in Hollywood.

While some fans love to see their favorite characters on the big screen again and again, others are unsatisfied with the quality of these sequels or even concerned about what they mean for the art of filmmaking. But are franchises actually getting worse with each movie?

This question isn’t exactly new, and others have used data-driven approaches to analyze it before — so let’s study and learn.

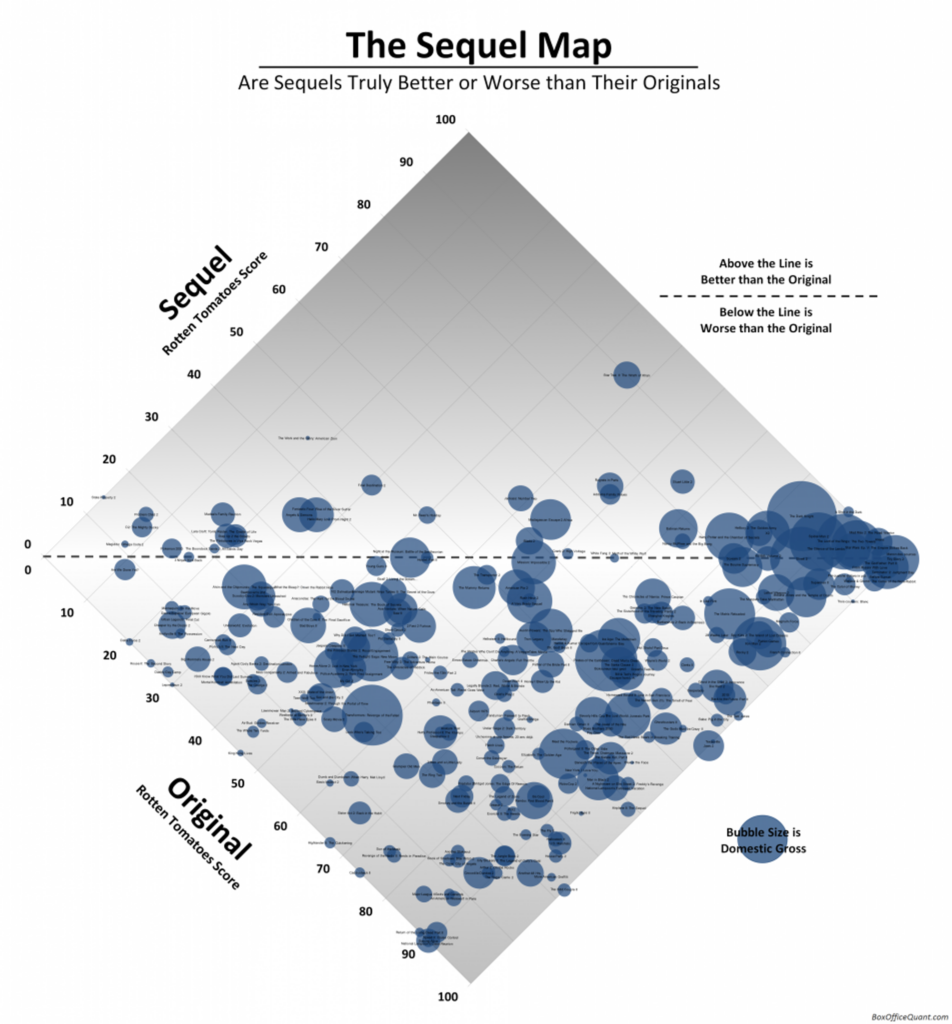

The most prominent visualization is probably “The Sequel Map,” published on the blog BoxOfficeQuant back in 2011. It shows that the second movie in a series is rated as worse than the original by Rotten Tomatoes users in the majority of cases.

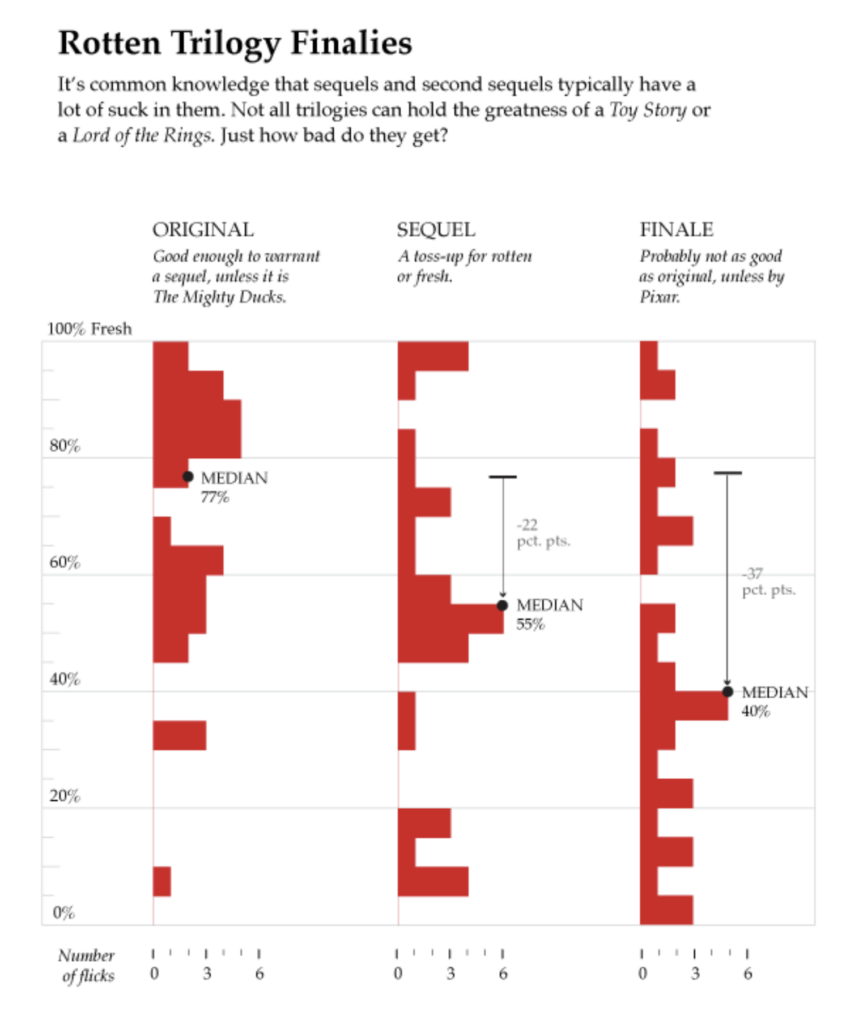

A year before, in 2010, Nathan Yau of FlowingData wrote specifically about movie trilogies getting worse over time, finding that, in his sample, third installments rated almost 40% worse than the originals on Rotten Tomatoes.

For my Weekly Chart, I aimed to come up with a visualization that can compare series of different lengths, showing the overall trend in franchises as they get longer.

In a world of prequels, sequels, spin-offs, remakes, and reboots we first need to define what a franchise even is. Fortunately, my favorite movie rating website Letterboxd offers a list of film “collections,” which I could conveniently use as my set of franchises — getting me out of the way of fiery debates. It should be noted that they seems to include only movies that occur in the main story line, with spin-offs often forming their own collections. (For example, the “Toy Story” Collection does not include the “Lightyear” spin-off.) It’s also important to mention that my analysis is based on the order of release and not the order of plot events, so “prequels” and sequels are treated the same.

For the points on my chart, I decided to cherry-pick a few franchises I consider interesting and well-known. The averages shown, however, are based on all Letterboxd collections.

While the first two charts paint a clear, devastating picture, extending the franchise length in my chart offers a glimpse of hope. For the first four to five installments, movie quality can be expected to decrease with every new sequel.[1] However, it seems that franchises that make it beyond that tend to stabilize in quality — part seven isn't particularly worse than part eight.

Another aspect of the negative sentiment towards movie franchises is the sense that franchises are "taking over Hollywood." To see how true that is, I looked at the top 250 Letterboxd movies of each year (as a proxy for the major new movie releases of the year) and calculated what percentage of these movies were part of a franchise.

Interestingly, there was a first wave of franchise movies in the '40s, with stories around fictional characters like the East Side Kids, Andy Hardy, and Michael Shayne spawning of dozens of movies within just a few years.

This trend had worn off in the '50s, and there's been a clear second wave of franchise movies from the '50s to the 2000s. Since then, the fraction of sequels has stagnated at around 12% of new releases — though more recent movies may yet become the "originals" of new franchises.

Another interesting tendency: More than a third of franchises whose first installment ranked in the year's top 250 did not make it into the top 250 with their second release. Since these rankings are based on user engagement and not just ratings alone, means that second parts are also significantly less known, not just less loved.[2] This trend also seems to be reflected in ticket sales, to such a degree that Disney has announced plans to reduce its franchise movie output. Maybe we are close to a peak like in the '40s? But what if not — is the future all franchise?

Along with the relative increase in franchise movies, there's been a great increase in the total number of movies released each year. This trend has held for the past 100 years and only accelerated since the turn of the millennium (despite a COVID-era dip). It's the result of many factors, the most important probably being technological advances and the resulting decreases in cost and facilitated access to equipment. It seems likely to me that with global social and economic development, movie output will continue to increase in the foreseeable future.

Even if, let’s say, 90% of new releases were franchise movies, there would still be over a thousand new, original movies released next year, three per day. In other words: Movie enthusiasts who dislike franchises will not run out of (interesting) new films to watch, but they might have to dig a little deeper to find what they're looking for.

I really enjoyed jumping in the role of a data journalist for the first time — although this article would not have turned out half as good without the amazing support from my colleague Rose. I hope you enjoyed it, but for now I’ll get back to writing code and join you in eagerly waiting for next week’s Weekly Chart article from our designer Alex.

All data is obtained from Letterboxd using a few custom scrapers and data analysis scripts. You can download my versions of the data sets on Kaggle.

Comments