Radish to romanesco: A year in vegetables

February 20th, 2025

4 min

This article is brought to you by Datawrapper, a data visualization tool for creating charts, maps, and tables. Learn more.

A writing system with three scripts & thousands of kanji characters

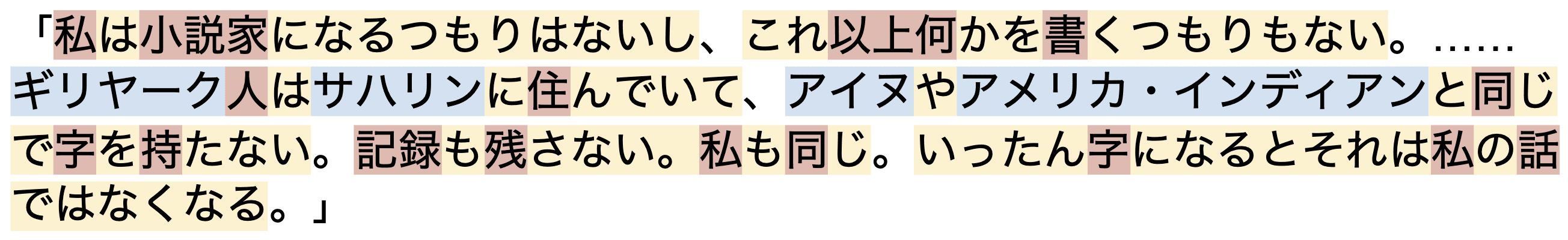

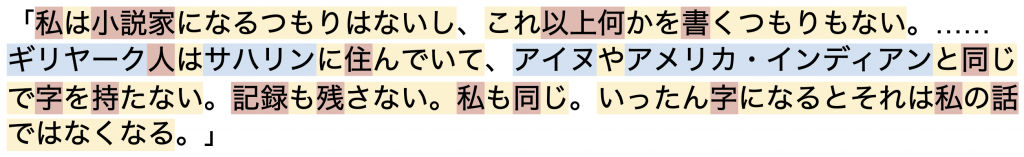

Hi, this is Aya from the support team. The other day, my colleague Eddie asked me how many kanji characters I knew. Kanji is one of three scripts that we Japanese use in our written language. I never gave much thought to it until now. So this week, I decided to do some research to revisit a language I call home. Here are my notes on what kanji are, why they made my childhood miserable, and why I love them nevertheless.

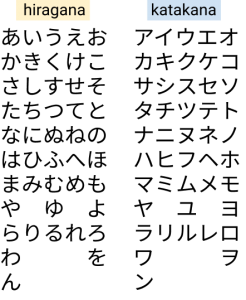

Hiragana and katakana are syllabaries: each character represents the sound of a single syllable, like ka, gi, or su.

Hiragana is the first script we learn as kids in elementary school. There are 46 characters and the entire spoken language can be written using these 46 syllables. Most of my earliest diary entries are only written in hiragana.

The next script we learn is katakana, which is kind of like a twin brother of hiragana. Katakana also has 46 characters that represent the same sounds as hiragana. The key difference here is what we use them for. They are mainly used for loan words from other languages.

Both kinds of characters are simple and can be written in 1-4 strokes. But hiragana is curvier while katakana is more square. Can you see the difference?

English may only have 26 letters in the alphabet, but each letter can represent different sounds in different contexts (like the letter c in

“cat” vs “city”) and has a far more complex syllable structure. In contrast, the Japanese syllable structure is simple and limited and only has 46 sounds.

This is why, in Japanese, there are many homophones – words that are pronounced the same but have different meanings.

You have this in English too – like meat and meet or buy, by and bye. They can be distinguished by their spellings and the context they’re used in. In Japanese, we replace homophones with characters from a third script: kanji.

Each kanji represents one meaning (morpheme) and can be read in multiple ways depending on the context.

For example, my name, “Aya,” is a very popular name and I have personally met dozens of Ayas in my life. But never have I met anyone with the exact same spelling. That’s because there are different characters that can be read “Aya,” each with its own meaning:

文・彩・綾・鮮・紋・彰・礼・章・郁

This is great because you can feel unique and special without having a bizarre-sounding name.

This also takes us back to my colleague Eddie’s original question. How many kanji characters do I know?

The Ministry of Education in Japan lists 2,136 characters to be taught in school. They are called Jōyō kanji which literally translates to “regular-use Chinese characters.”

And here’s a table of what they look like.

Now, seeing this list takes me back in time. Looking back, kanji learning may have been the source of all my misery throughout my school years. Here’s why.

From the age of six, we learned one kanji every day for homework and had weekly tests. We used something called “Kanji drills” where we simply wrote A LOT. We also had some calligraphy classes which I have to thank for my somewhat legible handwriting. Kanji was the basic building block to express and communicate your understanding in any school subject.

On top of that, there are a few ways to read each kanji depending on the context. On average, there are two meanings per kanji — that’s 4,388 different ways to read 2,136 kanji characters.

That’s not all. When it comes to names, there are special kanji AND special ways to read them.

I really like my name, “Aya.” It’s simple and easy to pronounce—when written phonetically. My parents liked a particular kanji that is not part of the jōyō kanji but part of a group of 632 characters used for names called jinmeiyo kanji. The issue is that most people don’t know these special kanji, making it impossible for them to read my name.

These kanji can also have dozens of more readings specifically for use in names. This illegibility of my name written in kanji has caused numerous problems, like awkward first encounters where I had to remind the other person that it’s the kanji’s fault and not their lack of kanji knowledge that they couldn’t figure out my name. I had to constantly correct my teachers in every new class and every new school, not to mention lost documents and administrative confusion.

So, to answer Eddie’s question—how many kanji do I know? Well, assuming my kanji knowledge from school is intact and the numerous unusual kanji I learned from names and places, I’d say around 3000 kanji in total. And these are only a small portion of kanji that exist in the world. The largest dictionary in Japanese has more than tens of thousands of kanji.

Having 3 types of scripts and an infinite number of characters can sound overly complicated and utterly unnecessary. However, over the years I’ve grown to love them more for two main reasons.

A recent study showed that different spoken languages carry roughly the same amount of information per second. But when it comes to writing, some languages are more efficient than others. Twitter is a good example:

Japanese and Korean characters can convey twice as much information as English characters, for instance, and Chinese more than three times as much.

Our discovery of cramming, Ikuhiro Ihara

I find this to be very true. My notes take up less space, books have less volume and are easier to carry around (less intimidating too), and I feel like there’s a lot of meaning I can condense into a short phrase or a sentence.

Japanese doesn’t use spaces between words. Using a mix of three different scripts with distinct appearances makes word separation obvious enough not to need them.

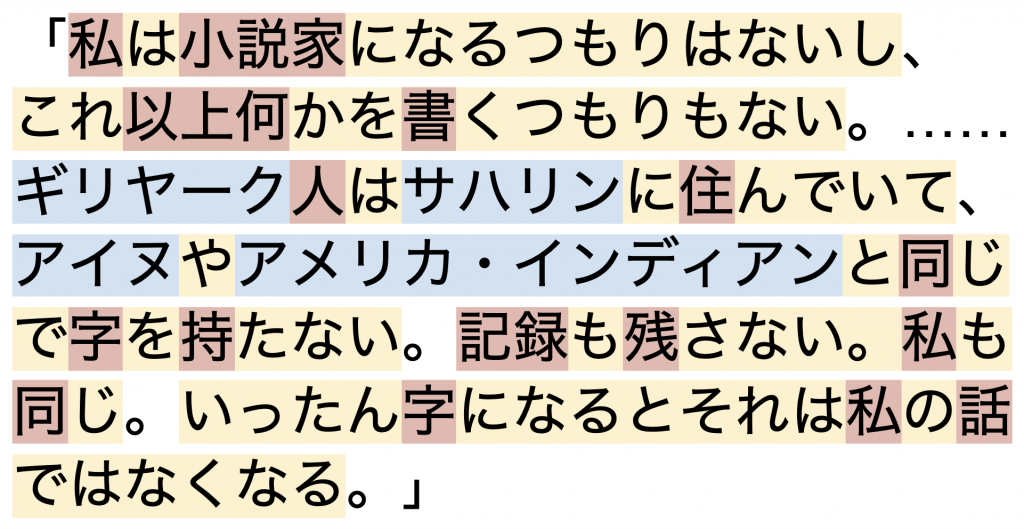

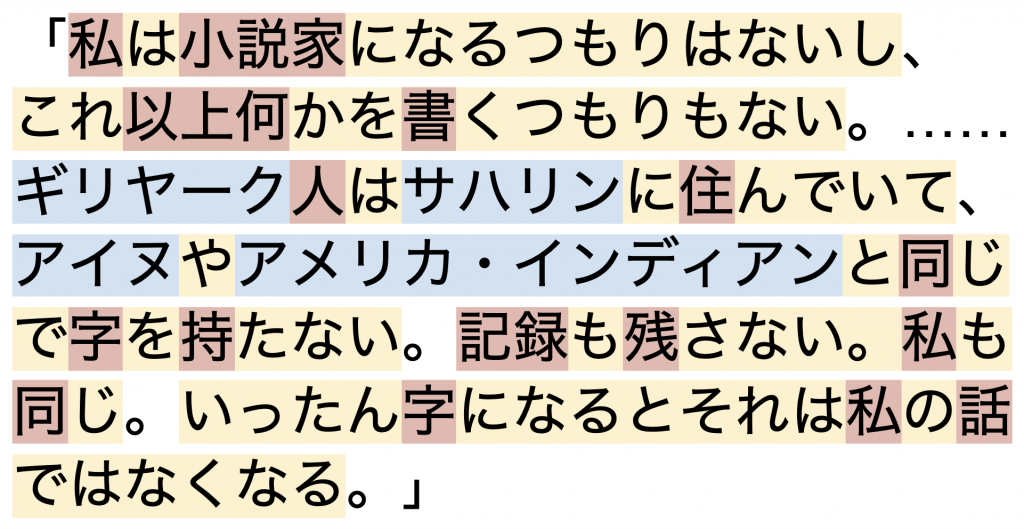

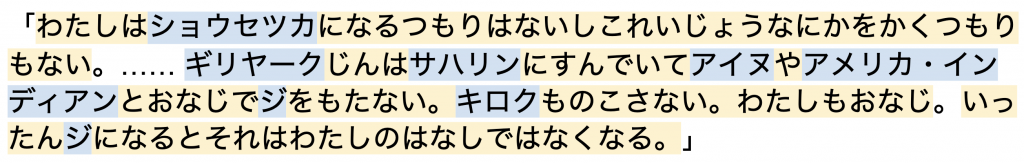

Here’s a little confession. The quote at the beginning of the blogpost actually looks like this in the original text, only comprised from hiragana and katakana:

For a Japanese-trained eye, this suddenly becomes a lot more difficult to read. It almost feels impossible to untangle the string of characters—and maybe that’s exactly what Murakami wanted me to experience. This particular text is a quote from one of the protagonists in the novel: a 17-year-old girl with dyslexia. It’s interesting how he conveys the experience of being dyslexic through the lack of kanji in a text.

kanji act as visual accents in the sentences, allowing us to distinguish separate words and identify sentence structure almost at a glance.[1] Having to learn hundreds of kanji to understand a written text might seem to make information less accessible. But what if it’s the opposite. What if it actually makes reading easier and more accessible, in a different way?[2]

This little bit of research allowed me to question why I read and write the way I do. I hope this makes you want to do some research into your own languages and writing systems too.

Thanks for reading! What writing systems and scripts did you grow up with? What do you use now and when do you use them? I’m curious to learn about your language journeys too. Feel free to drop me an email at aya@datawrapper.de or leave a comment below. See you next week!

Comments