The most common baby names are far less common these days

Hi, this is Lisa! I'm responsible for communications at Datawrapper. And this is my first Weekly Chart after seven months of parental leave – I'm excited to be back!

"What should we name our child?" That was the question my partner and I asked ourselves when I was pregnant last year. Twenty-five years after it became so popular in the U.S., my name, Lisa, was the most popular name for baby girls in Germany in 1991 and 1993 (I was born in 1990). I met a lot of Lisas when I was in school. And I did not like it. So when it was time to choose a name for our son and one of our favorites turned out to be at the top of the "most popular baby names" list for our region, I hesitated.

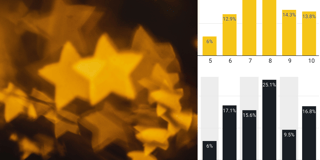

Turns out, there was nothing to worry about. Common baby names are less common today than they were thirty, fifty, a hundred years ago. Whereas in 1880 every 12th boy in the U.S. was named "John" and every 14th girl was named "Mary," today you'd need two hundred statistical babies to find the top names "Olivia" and "Liam" just once. This is a trend in many (Western) societies: In our region of Germany, the top boy's name in 2021 — the name we ended up giving our son — is still so rare that you'd need six classes of 25 kids to find it just once.

This is the case even though girls' names have traditionally been less conservative and more diverse than boys' names. In the area chart for girls' names above, you can see steeper but shorter peaks: the most popular girls' names became popular and faded out more quickly, and were never as common as the most popular boys' names. You can see the same phenomenon here:

What's behind the fall of the common name? There might be a few reasons, which are very much entangled:

- The rise of individualism in our societies has led parents to prefer names that stand out. "The Baby Boomers were the first parents who wanted to be cool, and who wanted their children to be cool as well,” author Pamela Redmond is quoted in this interesting BBC article. (I'm guilty of this, of course.)

- Less poverty, and therefore less uncertainty, results in a greater willingness to innovate and experiment, even with baby names. Psychology professor Michael Varnum says in this (different but also very interesting) BBC article: "When you have lots of resources and are less worried about scarcity, you can afford to stick out a little bit. In fact it may be advantageous to go away from the crowd. If you don’t have a lot of resources or wealth, the better strategy might be conformity and to do what most people are doing” — including giving the same baby names.

- Denser populations and the rise of radio, movies, television, and the internet means that more people are exposed to more possible names for their babies.

- Less religious societies lead to fewer religious, conservative names.

I find it astonishing. In the past months, I've met quite a few babies in Berlin: Theo, Henry, Levke, Johan, Leopold, Bordeaux... So far, none of them have shared a name.

If you want to experiment with the data yourself, you can get it from the U.S. Social Security Administration. Because they drop names with fewer than five occurrences, you'll also need to also download the total number of registered U.S. births from here if you want to calculate shares. See you next week!