Radish to romanesco: A year in vegetables

February 20th, 2025

4 min

This article is brought to you by Datawrapper, a data visualization tool for creating charts, maps, and tables. Learn more.

This is Zara checking in from Datawrapper. Some of you might have heard from me in Customer Support or occasionally in comments or messages on LinkedIn or Twitter. After Lisa’s last week’s article on #flattenthecurve, this week’s Weekly Chart is a hiatus from numbers, social distancing, and work in the time of Coronavirus (with apologies to Gabriel Garcia Márquez).

“W. H. Auden once suggested that to understand your own country you need to have lived in at least two others. One can say something similar for periods of time: to understand your own century you need to have come to terms with at least two others…”

Ian Mortimer, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England: A Handbook for Visitors to the Fourteenth Century

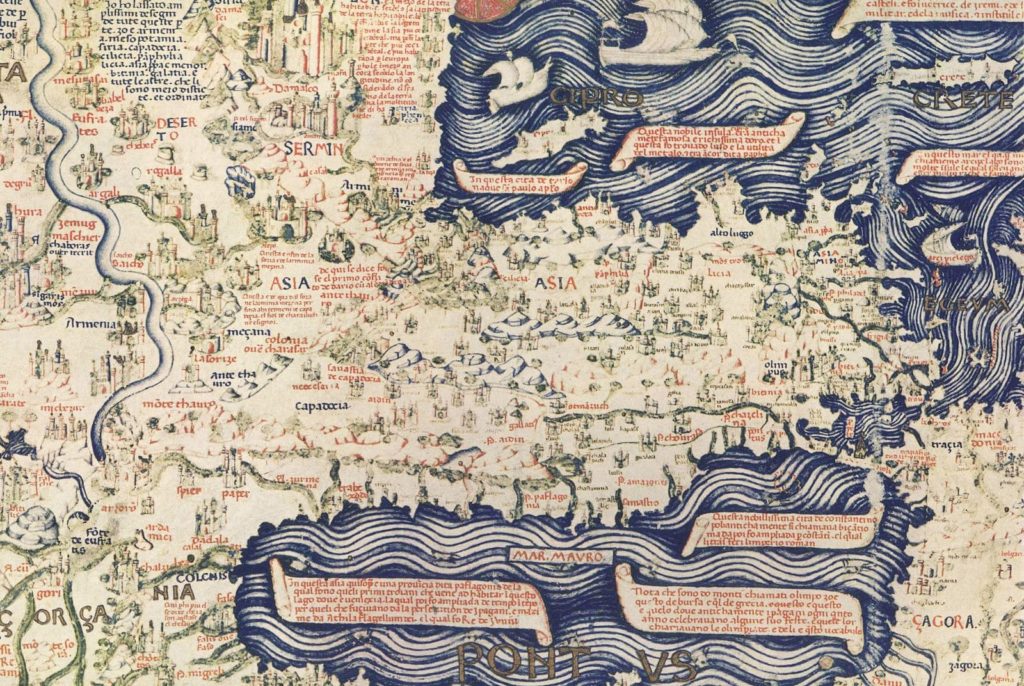

Exploration served as the bedrock in medieval times for opening new avenues of trade and connecting far-flung countries to each other. It’s true that several of these trade routes were key in wars or served as pathways for transmitting horrific pandemics across the continents. But they also helped people understand how life was in other parts of the world as well as acting as a catalyst in transmitting knowledge, ideas, commodities, and culture. However, undertaking these journeys was no easy feat, given the numerous obstacles like the fear of robberies, diseases, and long-term provision of money and food.

So it is no surprise then that some of the most well-known travelers of the middle ages embarked on long-distance journeys either under the auspices of the emperor of their times or because they came from affluent families. Though several notable explorers from the past (think Columbus) get a bad rep for the things they did to local communities during their visit, not all explorations or long-distance travels were motivated by a desire to colonize. This article explains the journeys taken by two such travelers.

The two most well-known travelers of the late 13th and early 14th centuries are Ibn-e-Battuta and Marco Polo. Ibn-e-Battuta (1304-1368) hailed from a family of legal scholars in Tangier, Morocco and set out on his journey all alone at the ripe age of 21 in 1325 to find new teachers and libraries. During his travels, he crossed several countries in the Middle East (Mecca, Baghdad, Damascus) before traveling to East Africa and then continuing across Central Asia, South Asia (primarily India), and South-East Asia until he reached China.

He didn’t stay very long in China and, after a brief stay in Tangier, set out once again to Spain and West Africa. He finally returned home from Africa on the emperor’s orders and told his travelogue to a young scholar in Tangier. While many of the parts from his book “The Rihla” (Arabic for “Voyage”) might be factually inaccurate, it does not reduce the incredible value of his work as it provides written sources about a time where sources of written nature were otherwise a rarity.

The year before Ibn-e-Battuta set out on his journey marked the passing away of a great Venetian explorer by the name of Marco Polo (1254-1324). Born in a family of merchants, his home town served as the crossroads for trade between Europe and Asia. In 1271, he set out on his first journey at a mere 17 years of age with his father and uncle. Polo did not get to see Venice for another two decades. His talents and diplomatic prowess convinced the Chinese emperor to assign him various responsibilities within the kingdom.

When Polo finally returned to Venice in 1295, twenty-four years after he left home, he was taken prisoner because of a war going on between Venice and Genoa. During imprisonment, accounts of his journeys were penned down by another inmate who was a writer of romances. Just like Ibn-e-Battuta, Polo’s work is not 100% historically accurate; there are loopholes and inaccuracies at several places in his book titled “The travels of Maco Polo”. It is seminal, regardless, because it was the first detailed account of a world outside Europe in the 14th century provided by a European traveler.

Maps are wonderful for bringing hundreds of pages into a concise portrayal as well as offering new insights that may very well be missed when reading (for example, did you notice how many cities on the map did both Ibn-e-Battuta and Marco Polo cross twice?).

I used a Datawrapper locator map for mapping the cities visited by these travelers during their epic journeys. For importing the line markers in GeoJSON format, I used the open-source tool geojson.io. The rest of the edits were made within Datawrapper’s map editor.

Creating this map was my attempt to bring historical journeys of mid-century travelers to life using an interactive chart. Thanks so much for reading! Comments, criticism, feedback? Feel free to get in touch via Twitter at @zara_k01. See you next week! (And until then, #stayhomesavelives.)

Comments