What to consider when choosing colors for race, ethnicity, and world regions

October 9th, 2024

11 min

This article is brought to you by Datawrapper, a data visualization tool for creating charts, maps, and tables. Learn more.

Imagine that you and I (and all the other readers of this article) are the graphics team of a new newspaper in a new country. The first election in this country happened yesterday. And we want to report the results. So we create charts and maps, showing how many voters voted for each party. For that, we need colors that represent each party.

But which colors? That’s exactly the question this blog post will explore. We’ll talk about three ways to assign colors to political parties: To take their party colors, to take political colors, or to just assign colors arbitrarily. While we’re at it, we will look at the colors of parties in Germany, the UK, and the US:

1. One party = one color: Germany

2. Too many parties, too few colors: The UK

A short excursion Less important parties, more important parties

3. Two parties, no colors: The US

Let’s begin!

When deciding on colors to represent each party in our charts and maps, our first idea might be to use the colors with which the parties present themselves: Which colors are used by parties in their logos? Which ones do they use on their campaign posters? These are the party colors.

Let’s look at German parties as an example. Here we can see the colors that they define as brand colors in their style guides. (Clicking on the party name next to the colors will bring you to the PDF style guides. Except for the AfD, for which I couldn’t find a style guide online.)

This is so not helpful. The two biggest parties in the country, SPD and CDU, both have almost the same red as their logo color. The party colors don’t help to distinguish clearly between parties in this case.

But we have another option: Instead of party colors, we can use political colors. Political colors stand for ideologies. E.g., we associate environmental movements with the color green. And in many countries, yellow is associated with liberalism, red with socialism, black with anarchism, blue with conservatism. (The Wikipedia article “Political colour” has a great overview).

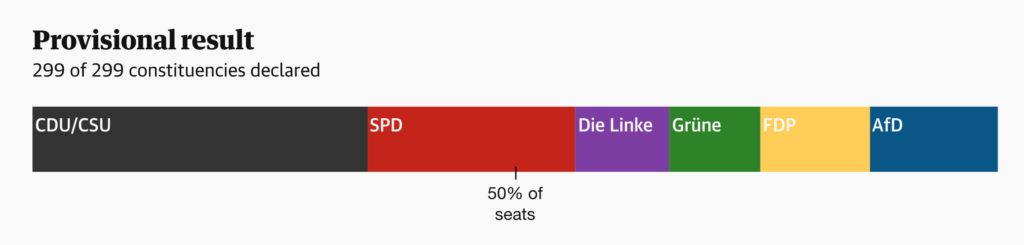

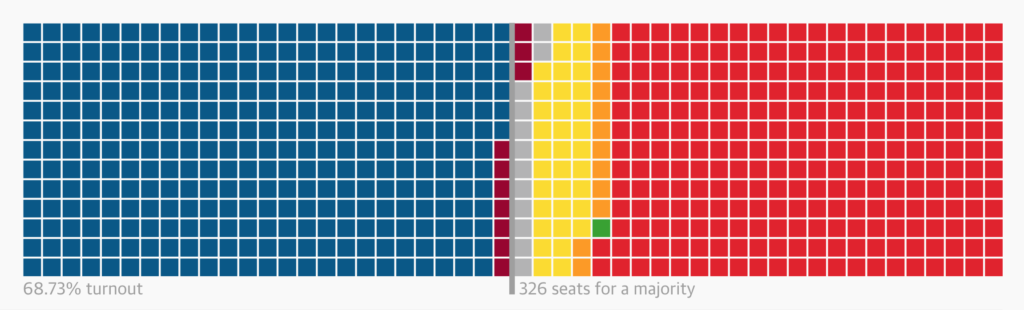

The Guardian: German election results 2017

Newspapers show many German parties with these political colors that are associated with the ideology the parties advocate for. The social democratic party SPD is represented by red, the Greens are green and the Liberals (FDP) yellow. The conservative party CDU (and the “Union”, the fusion of CDU and its Bavarian sister party CSU) was historically represented by blue, grey or black. By now there is the consensus to represent this party using black. And since blue is only used by the Bavarian CSU, it was still free to take on the national level for the newest important member in the German party family, the right-populist party AfD.

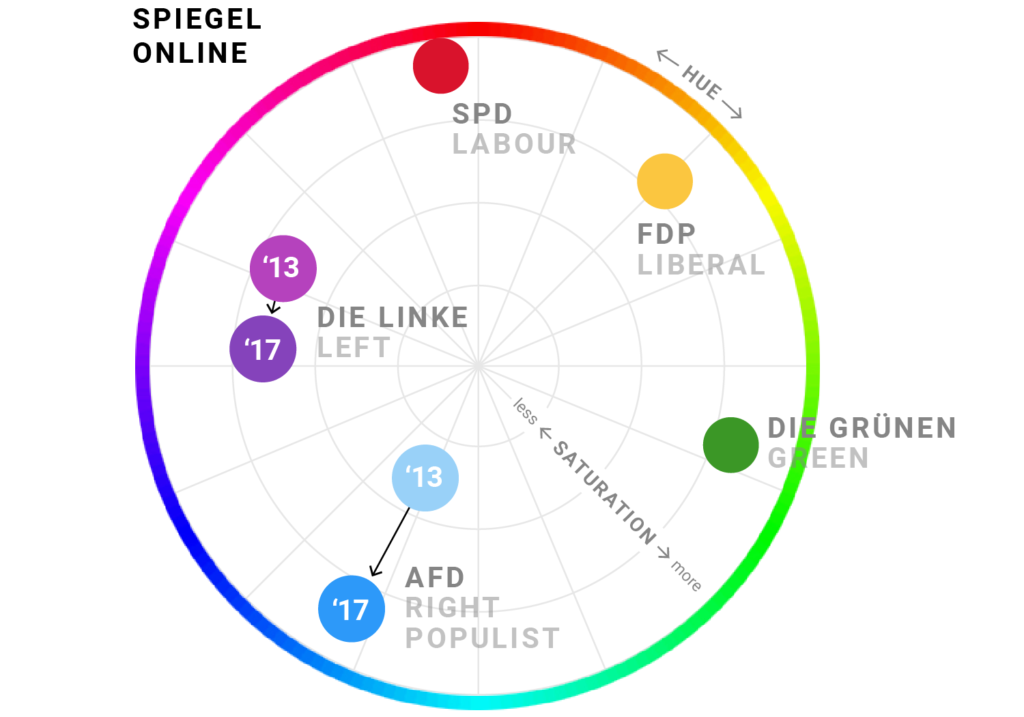

Here are the colors that different newsrooms inside and outside of Germany chose to represent parties during the last two general elections in 2013 and 2017.

You will find that the only party for which the color definition varies somewhat is The Left: Are they purple? Are they pink? It’s not quite clear:

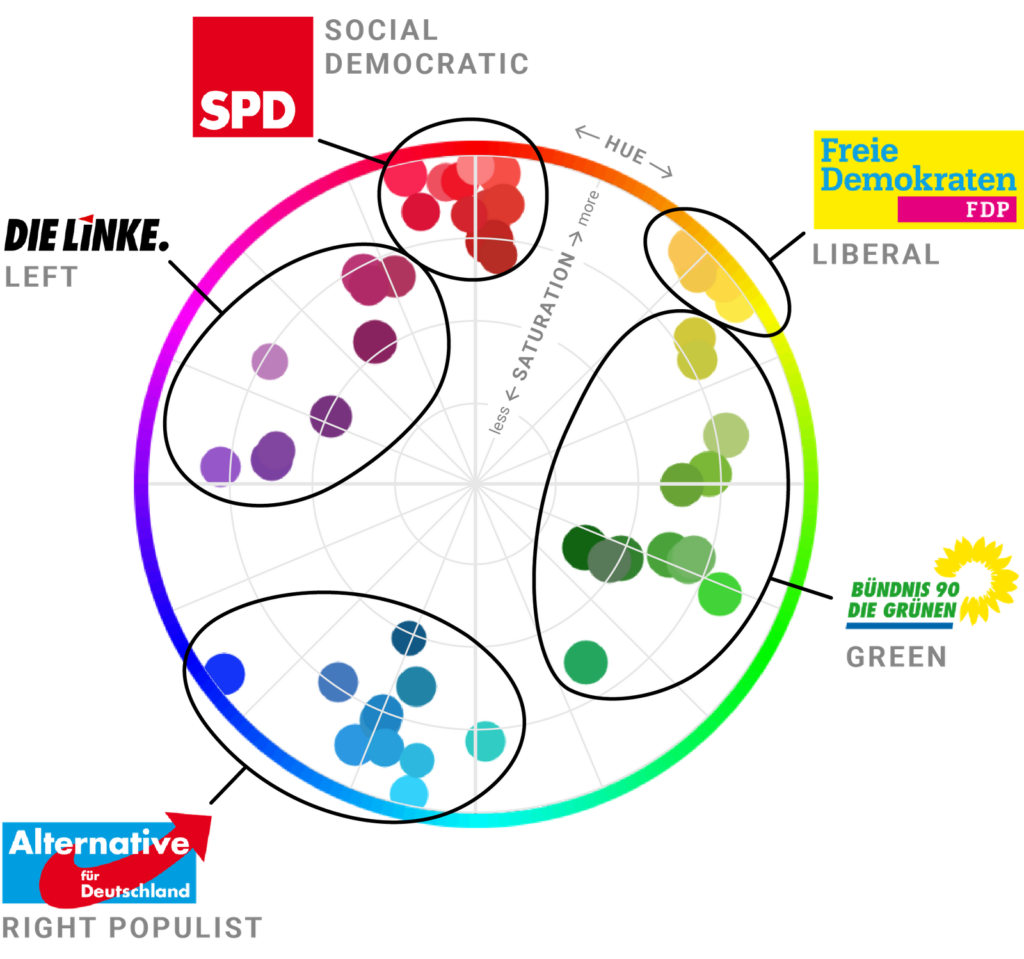

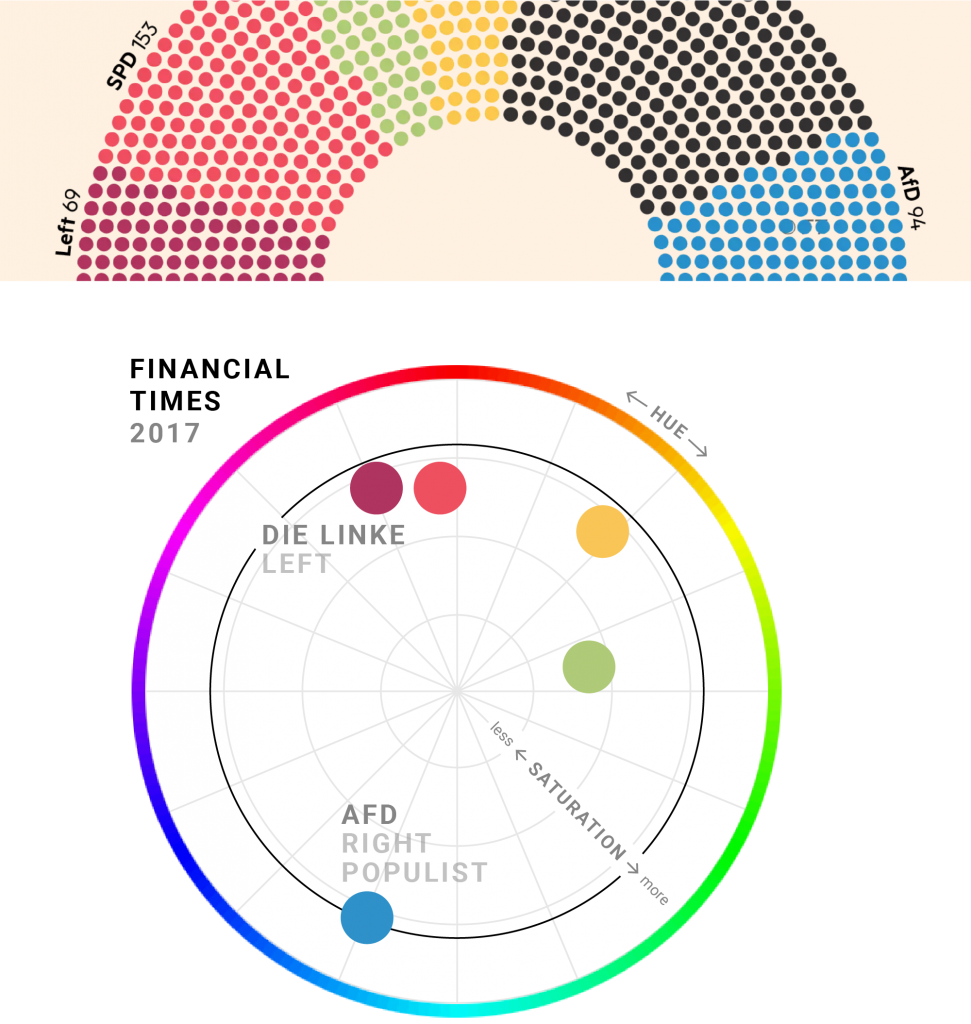

In general, we can see that there are barely any colors that overlap: Each color represents one, and just one party. We can show the colors from the collection above on a color wheel to make that point:

Some explanations: The closer the color is to the center, the less saturated it is. The saturation has nothing to do with lightness: A dark green doesn’t need to be very saturated. And you won’t find the CDU and it’s black/grey color on this wheel because all shades of grey are just boringly in the middle of a color wheel.

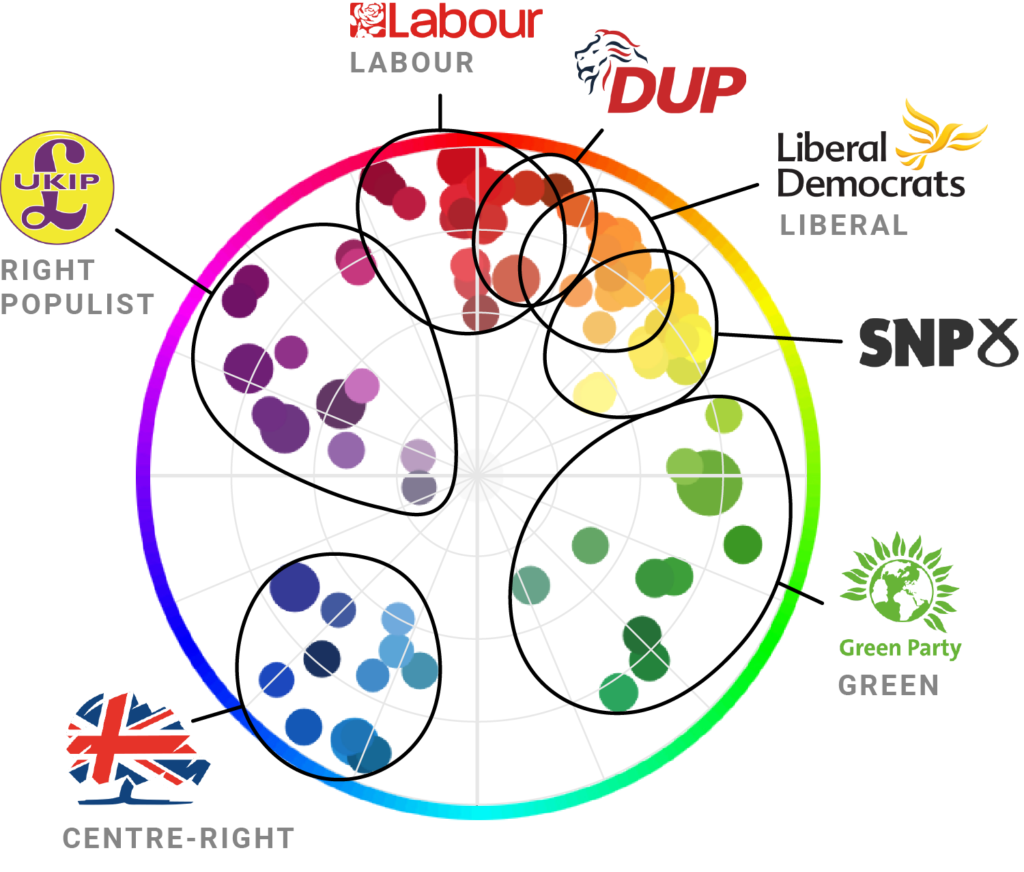

But not every country has just five to six parties that will get a significant number of votes. The same color wheel for parties in the UK looks far more chaotic, with overlapping colors:

So what happens if we need colors for more than just a few parties; especially if they all have similar party / political colors?

In the UK, that’s exactly the problem. The Labour party is red, like in many other countries. But the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is also shown in red:

Or does the DUP come in blue? There doesn’t seem to be agreement on that yet:

And on the color wheel we can see that UKIP (which is purple) strongly pushes into the realm of the red Labour color (more so than the Left’s purple pushes into the SPD’s red in Germany); while the Liberal Democrats (LD) try hard to not be red enough to be confused with Labour and not yellow enough to be confused with the Scottish National Party (SNP).

Ok, I’m not being fair here.

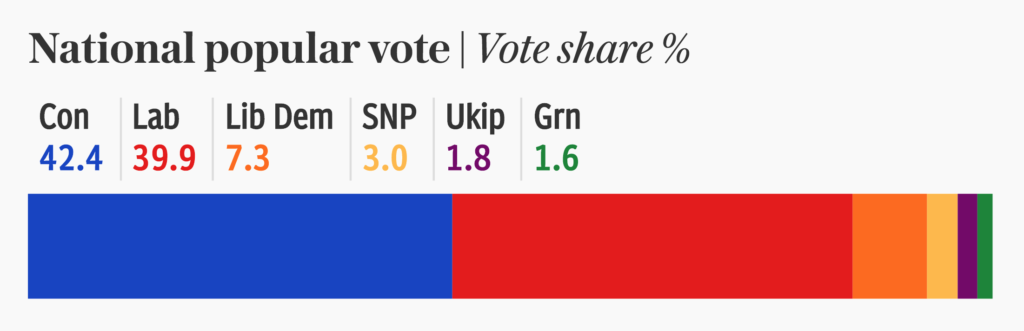

No UK newspaper actually sorts the parties like I did – and this sorting makes a huge difference. The colors of the main parties are quite clear,

The Telegraph: General Election 2017 results

The Guardian: UK election 2017 results

and less than 1% voted for DUP in the 2017 election – the party that also comes in red –, which makes them not interesting enough for overviews. Still, these parties are important enough to be shown in election reporting of all newspapers, e.g. in local reporting. I find it fascinating how different newspapers handle so many parties with similar colors:

Speaking of importance of parties: Color is an excellent way to make elements stick out visually, and newsrooms use that power. To explore an example, let’s go back to Germany:

Founded in April 2013, the right-wing populist party “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) got an astonishing 4.7% of the votes at the federal election in September 2013. Not quite enough to get into the parliament (there’s a 5% electoral threshold in Germany) – but most German media showed their result anyway. The German news site SPIEGEL ONLINE did so and chose the following colors:

Fast forward four years. In 2017, AfD convinced 12.6% of German voters to vote for them. The party moved into the parliament and was suddenly a huge topic in the media.

SPIEGEL ONLINE only changed the colors of two parties between 2013 and 2017: The color of the Left became a bit bluer. But the color of the AfD became way more saturated and darker:

Choosing the same desaturated light-blue color for this suddenly important party wouldn’t have felt appropriate. The AfD has now fully arrived on the political landscape in Germany. And the color had to reflect the change:

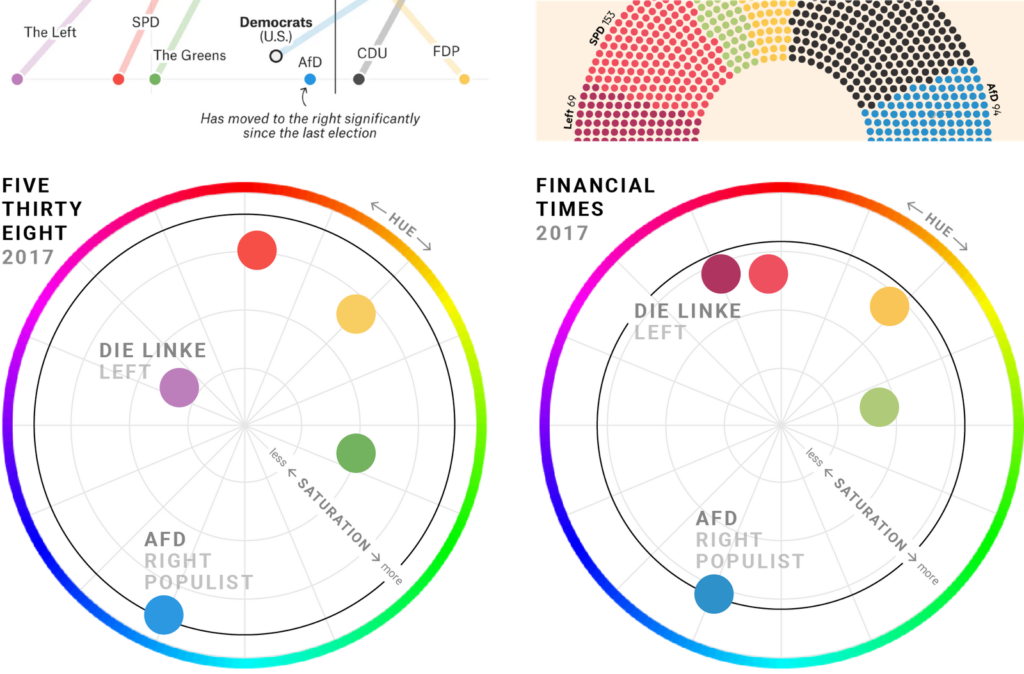

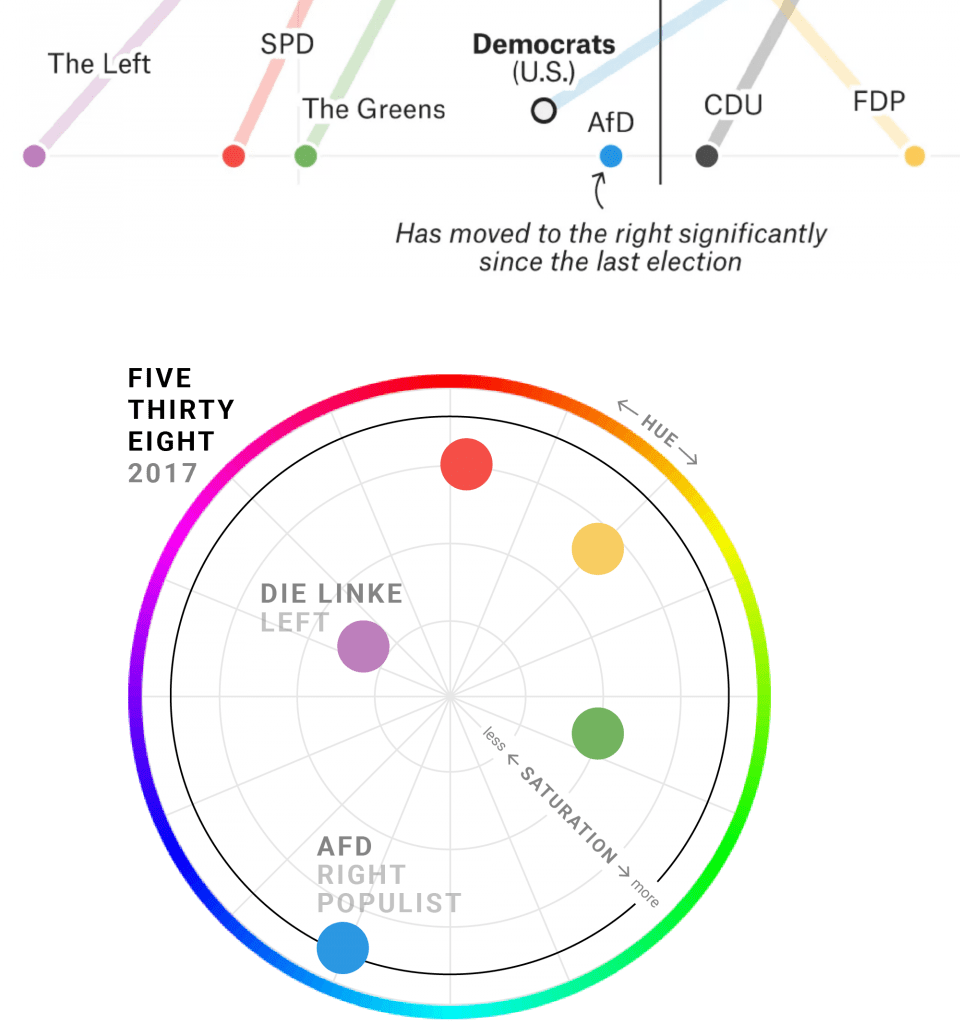

The Financial Times and FiveThirtyEight made a similar decision. While SPIEGEL ONLINE gave the AfD the same visual weight as the other big parties, the FT and FiveThirtyEight went one step further and made them stick out, if only slightly:

Above, you can see screenshots from the election tracker of the Financial Times and the article “Six Charts To Help Americans Understand The Upcoming German Election” by FiveThirtyEight. Below, you can see the party colors which were used in the color wheel. In both cases, AfD is shown with the most saturated color of all parties.

You can create such a color wheel and check your colors with Laurent Jégou’s tool “Color relations and proportions of an image”.

Back to the actual problem: How do we assign colors to parties? If we fly over the big pond, things become weird. Everyone who’s only a little bit interested in US politics knows that Democrats are shown with blue and Republicans with red:

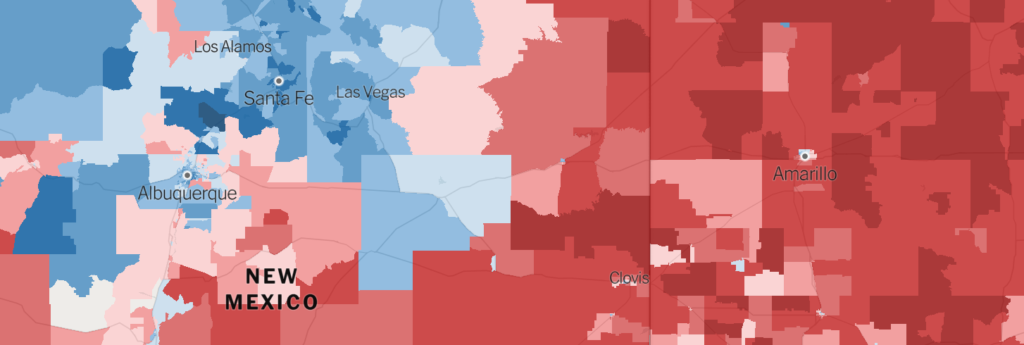

“An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2016 Election” by the New York Times, July 2018

But where does that come from? Both party symbols are red and blue, so it doesn’t come from the original party colors:

…and it doesn’t come from political colors: As we’ve learned earlier, red is associated with labour parties and blue with conservatism. That doesn’t really fit the US Democrats and Republicans.

The person responsible for the assignment of red for Republicans and blue for Democrats is…a graphics editor: Archie Tse. Well, the colors blue and red were used before Archie came along (they’re in the party symbols, after all). But there was no agreement yet on which party got red and which one got blue: “By 1996, color schemes were relatively mixed, as CNN, CBS, ABC, and The New York Times referred to Democratic states with the color blue and Republican ones as red, while Time and The Washington Post used an opposite scheme”, according to Wikipedia.

Four years later, senior graphics editor Archie Tse at the New York Times had to make a decision on which colors to choose for which party. “Red begins with R, Republican begins with R”, he thought, and hence, it was decided. Since the 2000 election, Republicans come in red and Democrats in blue.

Why were the colors decided so late, you ask? The main reason is technology: Colors have been only important since we can show them. TVs made their turn from black/white to color before newspapers, so they started thinking about which party colors to show to the audience first. The New York Times only turned into a full-color newspaper in 1997. And the mainstream use of the internet isn’t that old, either.

Here is a rather boring collection of the reds and blues that newspapers used to represent US parties in the 2016 election; sorted by the lightness of the Democratic blue:

It won’t come as a surprise that there is no consistency about the exact shades of red and blue within newsrooms – we’ve seen the same situation when we’ve looked at gender colors. Wikipedia articles from different languages don’t use the same colors:

Neither do articles by the Washington Post…

…nor by the New York Times:

By the way: It’s not all just blue and red in US politics. US-Newspapers actually put a lot of effort into charting and mapping primary elections, too. Which have many candidates. Who all need to be separated.

This is the time to dig deep into the confetti box! For example, here are the colors the New York Times used for candidates in the Virginia primaries in 2016:

The same candidates have differently assigned bonbon colors over at Bloomberg; maybe a hint less pastel than the ones by the New York Times:

That’s super colorful – almost as colorful as in the UK.

As we’ve seen, there are many reasons why thinking about party colors becomes necessary. New technology, a new party and too many parties (UK) are just three of them. And there is more than one strategy to assign a color: Choose the party color, choose a political color, and…choose a color that starts with the same letter as the party name (“Red”, “Republican”; thanks Archie).

Or just choose a color that isn’t assigned to another party yet. Because in the end, the color itself is not really that important. What’s important?

The US and Germany are past that finding stage; the UK is right in it. I’m looking forward to seeing them slowly agree over the coming elections.

Let me know about any interesting tidbits I missed or mistakes I made. Find me on Twitter or write me an email: mailto:lisa@datawrapper.de. Also, follow us on Twitter at @Datawrapper to not miss blog posts like this one.

Comments