Radish to romanesco: A year in vegetables

February 20th, 2025

4 min

This article is brought to you by Datawrapper, a data visualization tool for creating charts, maps, and tables. Learn more.

Hi, this is Eddie! Here at Datawrapper, I enjoy interacting with our users by answering their questions to support@datawrapper.de, managing our social media, and giving training sessions. When not at work, I like traveling and going on adventures. Since COVID-19 started, not much has happened on that end, so today, I would like to invite you to embark with me on a cruise down the Nile.

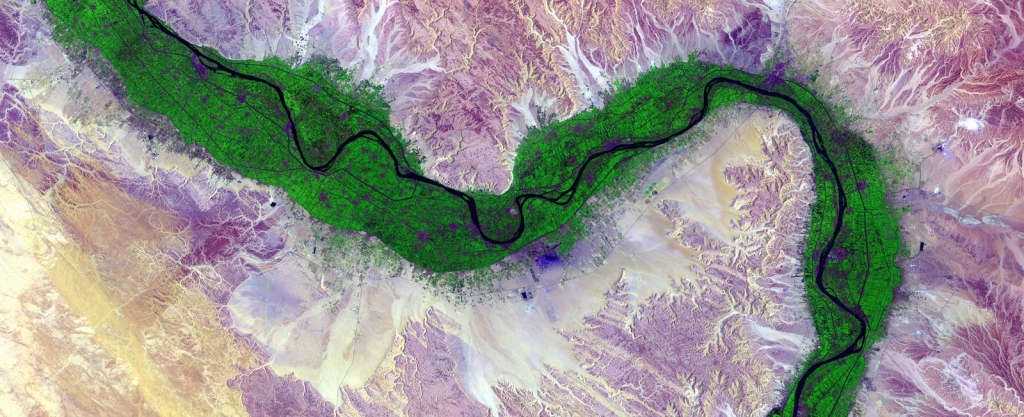

Considered to be the longest river in the world, the Nile passes through eleven countries in northeastern Africa, from Egypt to Tanzania. Well, it’s actually the other way around. While most rivers flow south, the Nile flows north, passing through Egypt to then empty into the Mediterranean sea. And that’s not the only remarkable thing about it.

For thousands of years, the Nile River invited communities to settle around it. This river is the primary source of water for countries like Egypt and Sudan and provides fertile land, transportation, and food for others as well, including Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and South Sudan. In Egypt alone, 95% of the population lives in the 4% of the country that make up the green belt around the Nile.

The Greek historian Herodotus defined the Nile as “a gift” to the Egyptians. And Egypt has historically adopted a strong approach to protect this gift. That changed in 1959 when Cairo agreed to share the Nile with its neighbor Sudan, awarding them a percentage of the total river flow. The agreement established that around 66% of its waters would go to Egypt, and 22% to Sudan, while the rest was considered to be lost due to evaporation. In 1929, Egypt had already signed another treaty with Great Britain, which gave Cairo the right to veto any projects related to the river, including building dams that could control its natural flow. None of these agreements took into consideration the needs of other Nile basin countries.

And then Ethiopia came into play. This country is home to the Blue Nile, one of the Nile’s main branches, and its highlands supply more than 85% of the) water that flows into the Nile River. In 2011, Addis Ababa announced the plan for the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. This $5 billion dam aims to boost the Ethiopian economy and become the largest hydroelectric power plant in Africa, generating around 6,500 megawatts of electricity.

The project was naturally received with discontent by Egypt and Sudan, who feared the dam could reduce or even “doom” their water supply. Despite negotiations having lasted for years, Sudan, Egypt, and Ethiopia have failed to reach a deal on how to share the waters.

Ethiopia’s dam was opened in 2020, but the conflict remains. Although several countries, like Russia and the USA, have tried to mediate in the conversations, the three countries don’t seem closer to an actual agreement. In the meantime, Ethiopia began filling the dam’s reservoir last July and expects that it reaches full power generating capacity in 2023. Addis Ababa hopes to fill up the dam within 4-7 years, while Cairo wants this process to take around 15 years to avoid that less Nile water flows to Egypt. The United Nations predicts that Egypt will likely experience water shortages by 2025 due to climate change, and Ethiopia’s new dam could worsen those shortages.

For Ethiopia, however, this new dam is key to their economic future. According to the International Energy Agency, in 2018, only 45% of the Ethiopian population had access to electricity, while 11% of its population was dependant on decentralized solutions, like petrol generators. The country hopes that, thanks to the dam, millions of its nearly 110 million citizens would get out of poverty and improve their living conditions.

The Nile River is a lifeline for Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan, but also an important source of water, food, and transport for the other countries where the river flows. Finding an equitable way to distribute it remains a challenge these countries will have to overcome.

To write this blog post, I gathered inspiration from many sources. These are just some of them:

And that’s all for this week! I hope you learned something new about the Nile and the complex geopolitics that surround it. Don’t hesitate to share your thoughts with me at edurne@datawrapper.de or my Twitter, @edurnemg. Next week is the turn for my colleague Lisa to write a Weekly Chart. In case you missed it, she published a four-part blog series on color scales this week, check it out!

Comments