What happened to the seven bridges in Königsberg?

February 2nd, 2024

5 min

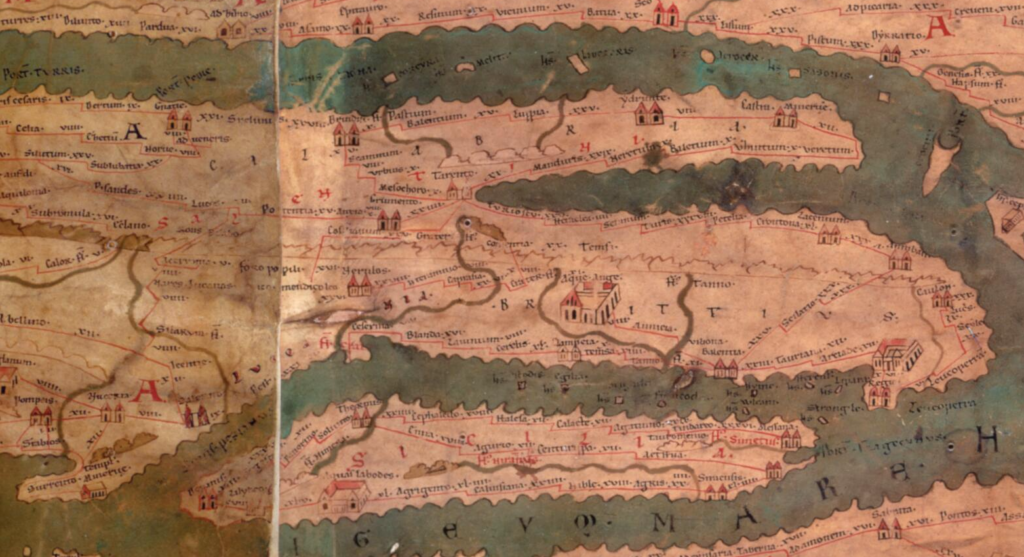

This map story is about one specific map, the only one remaining from the Roman Empire. The map is 6.8 meters long, 33 centimeters tall and spans from today’s western France to Sri Lanka and from Aswan in the south to The Hague in the north — almost the entire extent of the known world. It shows the routes of the Cursus Publicus, the state-administered road network for couriers and official transportation. We know it as the Tabula Peutingeriana.

Its name comes from the 16th century collector Konrad Peutinger, who owned the only copy of the map to survive the Middle Ages; it was made in the 1200s and consists of 11 separate parchment panels. There was most likely a 12th panel showing the westernmost parts of the empire, including Britain, the Iberian Peninsula, and Morocco, but it hasn’t survived to the present day.

The Cursus Publicus was initiated by Emperor Augustus in 27 BC to 14 AD as a fast, secure service for government and military communication and official travel around the empire. Stations were located at intervals of one day's travel along its roads, with all stations providing facilities to repair vehicles, change horses (or mules, or donkeys), and rest for the night. Some also offered extra amenities, such as baths, luxurious lodging, temples, or fortifications. This made it possible for Augustus to introduce a system of one courier carrying each parcel or message all the way to its destination, instead relaying them from person to person as in earlier times.

The roads carried traffic as well as messengers, but they weren’t open to just anyone; travelers had to carry a permit from the government or military stating their name, dates of travel, and the route and lodgings to be taken. Forging of permits was not uncommon.

At first glance, it’s hard to recognize the shape of Europe on this map. To fit the format of the panels, the geography is heavily stretched and distorted: the Italian peninsula, for example, takes up a third of the entire map and is rotated so that its length seems to run from east to west instead of north to south. Some elements of the natural geography such as water, forests and rivers are present, but all are very distorted. This isn’t because ancient people didn’t know what the world really looks like — the Ptolemy world map was well known at this time and cartography was a recognized field of science.

But if you just focus on the roads, which are drawn in red, it’s clear where they lead and how various cities are connected. In other words, the Tabula Peutingeriana does look like a modern map — a modern transit map.

A public transit map is usually not geographically correct; it shows only what you need to get from station A to station B. Any other information — scale, distance, the exact position of the stops, and features of the city other than its transit lines — is stripped off the map to make it as easy as possible for passengers to find their route. The most abstract transit maps, showing only lines and stations, can be described as mathematical graphs.

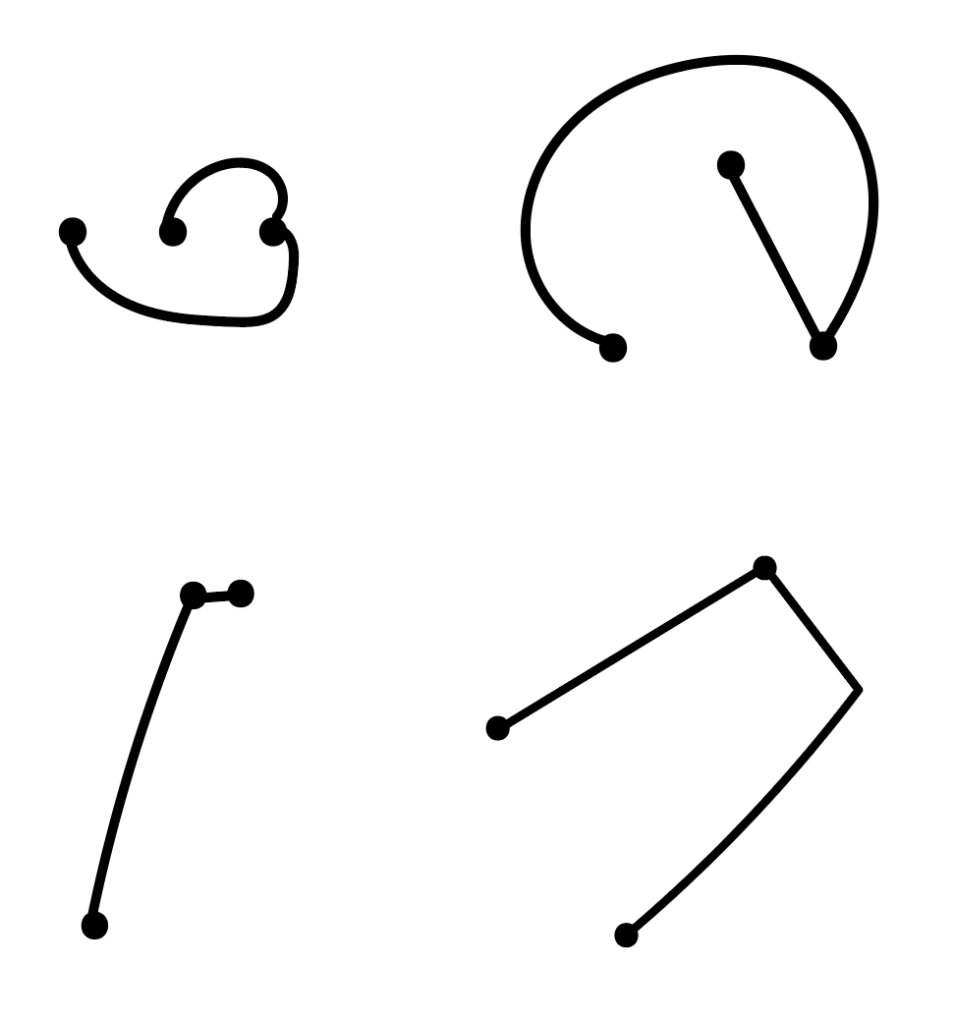

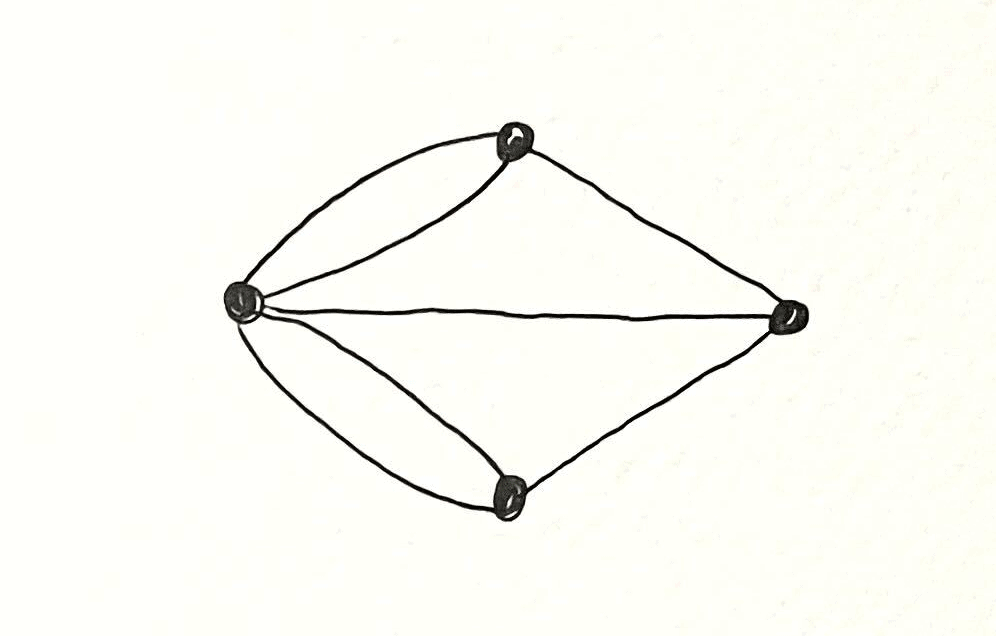

A graph is a mathematical object in which certain points, or vertices, are connected by lines, or edges. The nature of the graph is determined by the number of vertices and the particular way that the edges connect them. Everything else about it — where exactly we place the vertices, how long the edges are, whether they’re straight or curved or loopy — is irrelevant, mathematically speaking.

In fact, maps have been part of graph theory from the very beginning, ever since Leonard Euler introduced it as a field of mathematics in the late 1700s. In his paper on the seven bridges of Königsberg, he proved that in that city, where four land masses were connected by seven bridges, it was impossible to cross all seven bridges without crossing any bridge twice. What Euler did was to remove all features of the landscape except the land masses and bridges, and consider the land masses as vertices and bridges as edges connecting them. Since that graph preserves all the important information about how to get from one land mass to another (just like a transit map!), he could use it as a simple representation of the city in his proof.

Neither a modern transit map nor the Tabula Peutingeriana are cartographic maps — they are visualizations of graphs. The couriers’ stations are the graph’s vertices and each stretch of road connecting two stations is an edge. (In fact, the word tabula is a Latin term that can also mean chart, diagram, or figure.)

Just like in a modern transit map, zones with a lot of roads might be enlarged or distorted to show the network more clearly. This “distorted” view makes it easier to display the most important information: what route leads to your destination and which stations it passes along the way.

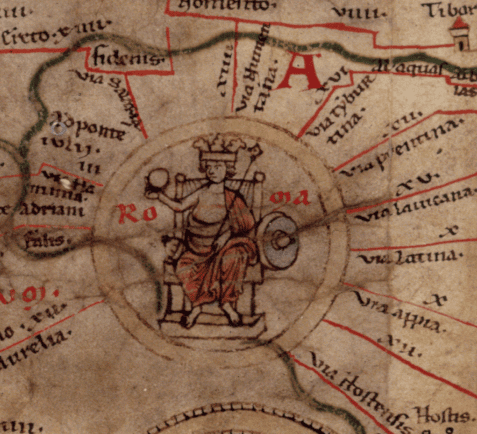

The map names 555 cities and 3500 other waystations. Each stop is marked with symbols showing the facilities on offer, including temples, harbors, public baths, and fortified walls. The most important cities — Rome, Constantinople, and Antioch — are marked with more decorated symbols.

Scholars think that travelers in the Roman Empire didn’t actually carry their maps on the road. They would have been inconvenient to copy out, and carrying around a seven meter long map sounds very impractical anyway. Instead, travelers would bring an itinerarium — a written list of destinations and their connections and distances to other cities nearby. These would have been cheaper to produce, so a traveler could easily get hold of an itinerary for the direction they were heading.

So when would the map have been used? Since there are no classical sources that mention the Tabula Peutingeriana, or any other road map, it’s hard to know exactly. It might have been used to plan longer trips in advance, or for political and military planning purposes.

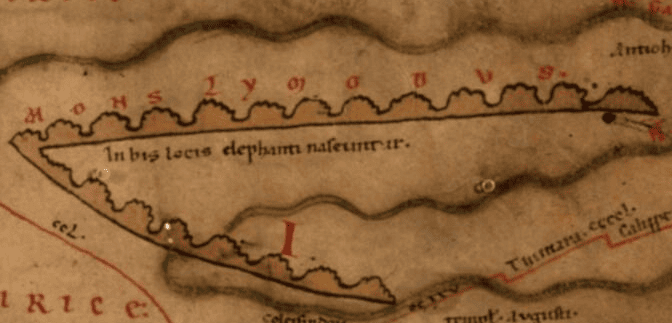

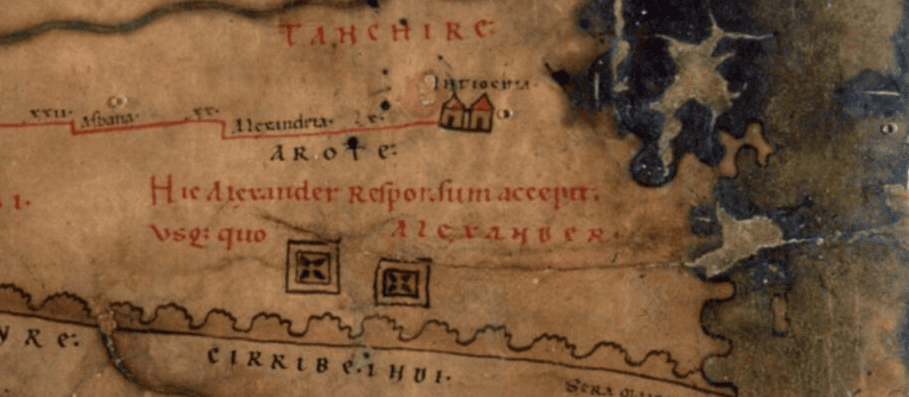

The map also includes some information that doesn’t seem practical at all. For example, over India is a note reading In hic locis elephanti nascuntur (“Elephants are born here”). The furthest extent of the empire of Alexander the Great, in modern Tajikistan, is also marked with the note Hic Alexander responsum accepit usq. quo Alexander (“Here Alexander received an answer [to the question]: How far, Alexander?”) Some researchers argue that the map was not only a tool for navigating, but also a way to display the power of the Roman Empire. Roads were more important than conquered cities; without roads, there would be no way to send messages, move military troops, transport food and trade goods, and keep the entire Empire together.

There is no exact date for the first version of the map. It must have been copied many times, but the only copy to have survived to our days was made around the year 1200, 700 years after the fall of the Roman Empire. Every time the map was copied, the person drawing it had a chance to make their own additions and mistakes. The result is that the map mixes different centuries, showing a reality that never existed at any single point in time.

For example, the city of Pompeii is marked on the map even though it was abandoned after the volcanic eruption of 79 CE. But the map also has “Constantinople” instead of Byzantinum (its common name until 500 CE) and “Jerusalem” instead of Aelia Capitolina (as it was known to the Romans from 135–324 CE). Sometimes roads even appear duplicated because the same city is shown multiple times under different historical names. Certain additions were clearly made by Christian copyists, like the spot in the Sinai desert reading Hic legem acceperunt i(n) monte Syna (“Here on Mount Sinai they received the law”).

There is no information on the whereabouts of the map from the time it was first produced until the surviving copy was made. That copy was rediscovered in the library of the city Worms in 1494, and most probably stolen from there by Conrad Celtes, a scholar and poet of the German Renaissance. Before Celtes died, he gave the map to his good friend Konrad Peutinger, whose family kept it for the next 200 years, giving it their name. For noble families in the Holy Roman Empire, artifacts that connected their empire to the ancient Romans had a special significance. The Peutinger family sold the map in 1714 and eventually in 1737 it was bought by the Habsburg Imperial Court Library in Vienna — now the Austrian National Library — where it still lives today.

Thank you all for a great first year of Map Stories! We'll see each other in 2024.

Comments